Marriage, as a social institution, has been around for thousands of years.1 With things that are thousands of years old, it is easy to assume that they can only change slowly. But developments since the middle of the 20th century show that this assumption is wrong: in many countries, marriages are becoming less common, people are marrying later, unmarried couples are increasingly choosing to live together, and in many countries, we are seeing a ‘decoupling’ of parenthood and marriage. Within the last decades the institution of marriage has changed more than in thousands of years before.

Here we present the data behind these fast and widespread changes and discuss some of the main drivers behind them.

In many countries, marriage rates are declining

The proportion of people who are getting married is going down in many countries across the world.

The chart here shows this trend for a selection of countries. It combines data from multiple sources, including statistical country offices and reports from the UN, Eurostat, and the OECD.

For the US we have data on marriage rates going back to the start of the 20th century. This lets us see when the decline started, and trace the influence of social and economic changes during the process.

- In 1920, shortly after the First World War, there were 12 marriages annually for every 1,000 people in the US. Marriages in the US then were almost twice as common as today.

- In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the rate fell sharply. In the 1930s marriages became again more common and in 1946 - the year after the Second World War ended - marriages reached a peak of 16.4 marriages per 1,000 people.

- Marriage rates fell again in the 1950s and then bounced back in the 1960s.

- The long decline started in the 1970s. Since 1972, marriage rates in the US have fallen by almost 50%, and are currently at the lowest point in recorded history.

The chart also shows that in comparison to other rich countries, the US has had particularly high historical marriage rates. But in terms of changes over time, the trend looks similar for other rich countries. The UK and Australia, for example, have also seen marriage rates declining for decades, and are currently at the lowest point in recorded history.

For non-rich countries the data is sparse, but available estimates from Latin America, Africa, and Asia suggest that the decline of marriages is not exclusive to rich countries. Over the period 1990 - 2010, there was a decline in marriage rates in the majority of countries around the world.

But there’s still a lot of cross-country variation around this general trend, and in some countries, changes are going in the opposite direction.

Marriages across cohorts have declined

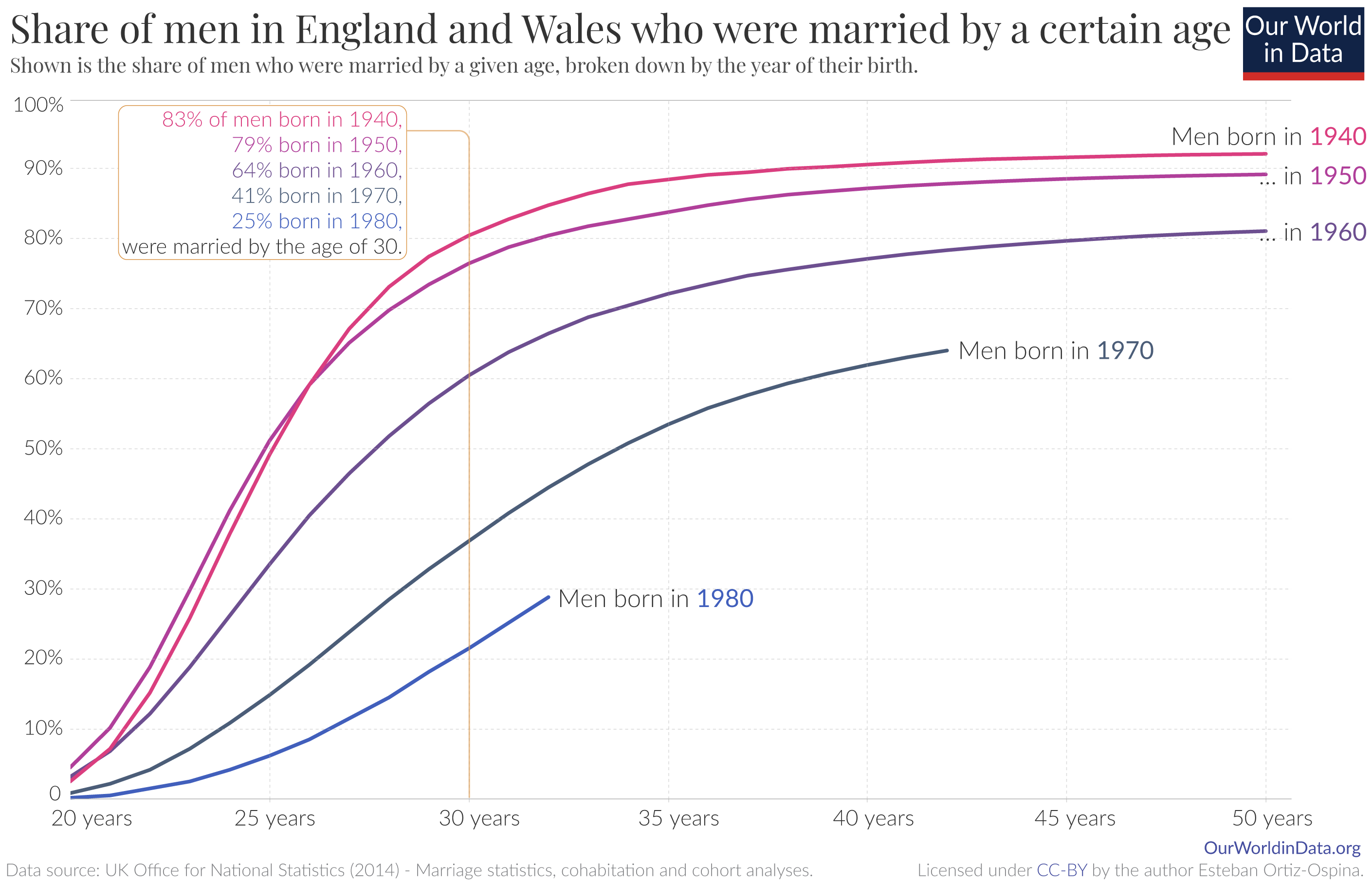

This chart looks at the change in marriages from a different angle and answers the question: How likely were people of different generations to be married by a given age?

In many rich countries there are statistical records going back several generations, allowing us to estimate marriage rates by age and year of birth. The chart here uses those records to give marriage rates by age and year of birth for five cohorts of men in England and Wales.

For instance, you can look at 30-year-olds, and see what percentage of them in each cohort was married. Of those men who were born in 1940, about 83% were married by age 30. Among those born in 1980 only about 25% were married by age 30.

The trend is stark. English men in more recent cohorts are much less likely to have married, and that’s true at all ages.

There are two causes for this: an increasing share of people in younger cohorts are not getting married; and younger cohorts are increasingly choosing to marry later in life. We explore this second point below.

People are marrying later

In many countries, declining marriage rates have been accompanied by an increase in the age at which people are getting married. This is shown in the chart here, where we plot the average age of women at first marriage.3

The increase in the age at which people are getting married is stronger in richer countries, particularly in North America and Europe.

In countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the average age at marriage has increased less or broadly remained unchanged.

More people marrying later means that a greater share of young people are unmarried.

According to the British census of 1971 about 85% of women between the age of 25 and 29 were married, as this chart shows. By 2011 that figure had declined to 58%.

For older people the trend is reversed - the share of older women who never got married is declining. In the 1971 census, the share of women 60-64 who had ever been married was lower than it is for women in that age bracket in the decades since.

You can create similar charts for both men and women across all countries, using the UN World Marriage Data site. This lets you explore in more detail the distribution of marriages by age across time, for both men and women.

The share of children born outside of marriage has increased substantially in almost all OECD countries

An arrangement where two or more people are not married but live together is referred to as cohabitation. In recent decades cohabitation has become increasingly common around the world. In the US, for example, the US Census Bureau estimates that the share of young adults between the ages of 18 and 24 living with an unmarried partner went up from 0.1% to 9.4% over the period 1968-2018; and according to a survey from Pew Research, today most Americans favor allowing unmarried couples to have the same legal rights as married couples.

The increase in cohabitation is the result of the two changes that we discussed above: fewer people are choosing to marry and those people who do get married tend to do so when they are older and often live with their partner before getting married. In the UK, for example, 85% of people who get married cohabited first.5

Long-run data on the share of people living in cohabitation across countries is not available, but some related data points are: in particular, the proportion of births outside marriage provides a relevant proxy measure, allowing comparisons across countries and time; if more unmarried people are having children, it suggests that more people are entering long-term cohabiting relationships without first getting married. It isn’t a perfect proxy - as we’ll see below, rates of single parenting have also changed, meaning that rates of births outside marriage will not match perfectly with cohabitation rates - but it provides some information regarding the direction of change.

The chart here shows the percentage of all children who were born to unmarried parents.

As we can see, the share of children born outside of marriage has increased substantially in almost all OECD countries in recent decades. The exception is Japan, where there has been only a very minor increase.

In 1970, most OECD countries saw less than 10% of children born outside of marriage. In 2014, the share had increased to more than 20% in most countries, and to more than half in some.

The trend is not restricted to very rich countries. In Mexico and Costa Rica, for example, the increase has been very large, and today the majority of children are born to unmarried parents.

Globally, the percentage of women in either marriage or cohabitation is decreasing, but only slightly

In recent decades there has been a decline in global marriage rates, and at the same time, there has been an increase in cohabitation. What’s the combined effect if we consider marriage and cohabitation together?

The chart below plots estimates and projections, from the UN Population Division, for the percentage of women of reproductive age (15 to 49 years) who are either married or living with an unmarried partner.

Overall, the trend shows a global decline - but only a relatively small one, from 69% in 1970 to 64% projected for 2020. At any given point in the last five decades, around two-thirds of all women were married or cohabitated.

There are differences between regions. In East Asia, the share of women who are married or in a cohabiting union increased, in South America the share is flat, and in North America and North Europe it declined.

Single parenting is common, and in many countries, it has increased in recent decades

This chart shows the share of households of a single parent living with dependent children. There are large differences between countries.6

The causes and situations leading to single parenting are varied, and unsurprisingly, single-parent families are very diverse in terms of socio-economic background and living arrangements, across countries, within countries, and over time. However, there are some common patterns:

- Women head the majority of single-parent households, and this gender gap tends to be stronger for parents of younger children. Across OECD countries, about 12% of children aged 0-5 years live with a single parent; 92% of these live with their mother.7

- Single-parent households are among the most financially vulnerable groups. This is true even in rich countries. According to Eurostat data, across European countries, 47% of single-parent households were “at risk of poverty or social exclusion” in 2017, compared with 21% of two-parent households.8

- Single parenting was probably more common a couple of centuries ago. But single parenting back then was often caused by high maternal mortality rather than choice or relationship breakdown; it was also typically short in duration since remarriage rates were high.9

Marriage equality is increasingly considered a human and civil right, with important political, social, and religious implications around the world.

In 1989, Denmark became the first country to recognize a legal relationship for same-sex couples, establishing ‘registered partnerships’ granting those in same-sex relationships most of the rights given to married heterosexuals.

It took more than a decade for same-sex marriage to be legal anywhere in the world. In December 2000, the Netherlands became the first country to establish same-sex marriage by law.

In the first two decades of the 21st century legislation has quickly spread across more countries.

Where are same-sex marriages legal?

This map shows in green all the countries where same-sex marriage is legal.

Many of the countries that allow same-sex marriage are in Western Europe. But same-sex marriage is also legal in other parts of the world, especially in North and South America.

Some perspective on the progress made regarding marriage equality

The rate of adoption of marriage equality legislation over time gives us some perspective on just how quickly things have changed. The first chart shows that in the year 2000, same-sex marriage was not legal in any country - two decades later it was legal in many more.

Changes in attitudes towards homosexuality are one of the key factors that have enabled the legal transformations that are making same-sex marriage increasingly possible.10

The second chart shows that the number of people living in countries that have legalized same-sex marriage has also increased a lot.

And as the third chart shows, same-sex sexual acts are now legal in a majority of all countries11.

Despite these positive trends, much remains to be done to improve the rights of LGBTQ people. In some countries people are imprisoned and even killed simply because of their sexual orientation or gender identity; and even in countries where same-sex sexual activity is legal, these groups of people face violence and discrimination.

Across the world, fewer people are choosing to marry, and those who do marry are, on average, doing so later in life. The underlying drivers of these trends include the rise of contraceptives, the increase of female participation in labor markets (as we explain in our article here), and the transformation of institutional and legal environments, such as new legislation conferring more rights on unmarried couples.12

These changes have led to a broad transformation of family structures. In the last decades, many countries have seen an increase in cohabitation, and it is becoming more common for children to live with a single parent, or with parents who are not married.

These changes have come together with a large and significant shift in people’s perceptions of the types of family structures that are possible, acceptable, and desirable. Perhaps the clearest example of this is the rise of same-sex marriage.

The de-institutionalization of marriage and the rise of new family models since the middle of the 20th-century show that social institutions that have been around for thousands of years can change very rapidly.

Trends in the rate of divorces relative to the size of the population

How have divorce rates changed over time? Are divorces on the rise across the world?

In the chart here we show the crude divorce rate - the number of divorces per 1,000 people in the country.

When we zoom out and look at the large-scale picture at the global or regional level since the 1970s, we see an overall increase in divorce rates. The UN in its overview of global marriage patterns notes that there is a general upward trend: "at the world level, the proportion of adults aged 35-39 who are divorced or separated has doubled, passing from 2% in the 1970s to 4% in the 2000s."

But, when we look more closely at the data we can also see that this misses two key insights: there are notable differences between countries; and it fails to capture the pattern of these changes in the period from the 1990s to today.

As we see in the chart, for many countries divorce rates increased markedly between the 1970s and 1990s. In the US, divorce rates more than doubled from 2.2 per 1,000 in 1960 to over 5 per 1,000 in the 1980s. In the UK, Norway, and South Korea, divorce rates more than tripled. Since then divorce rates declined in many countries.

The trends vary substantially from country to country.

In the chart, the US stands out as a bit of an outlier, with consistently higher divorce rates than most other countries, but also an earlier 'peak'. South Korea had a much later 'peak', with divorce rates continuing to rise until the early 2000s. In other countries - such as Mexico and Turkey - divorces continue to rise.

The pattern of rising divorce rates, followed by a plateau or fall in some countries (particularly richer countries) might be partially explained by the differences in divorce rates across cohorts, and the delay in marriage we see in younger couples today.

Economists Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers looked in detail at the changes and driving forces in marriage and divorce rates in the US.13 They suggest that the changes we see in divorce rates may be partly reflective of the changes in expectations within marriages as women enter the workforce. Women who married before the large rise in female employment may have found themselves in marriages where expectations were no longer suited. Many people in the postwar years married someone who was probably a good match for the postwar culture but ended up being the wrong partner after the times had changed. This may have been a driver behind the steep rise in divorces throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

The share of marriages ending in divorce

Trends in crude divorce rates give us a general overview of how many divorces happen each year but need to be interpreted with caution. First, crude rates mix a large number of cohorts - both older and young couples; and second, they do not account for how the number of marriages is changing.

To understand how patterns of divorce are changing it is more helpful to look at the percentage of marriages that end in divorce and look in more detail at these patterns by cohort.

Let's take a look at a country where divorce rates have been declining in recent decades.

In the chart here we show the percentage of marriages which ended in divorce in England and Wales since 1963. This is broken down by the number of years after marriage - that is, the percentage of couples who had divorced five, ten and twenty years after they got married.

Here we see that for all three lines, the overall pattern is similar:

- The share of marriages that end in divorce increased from the 1960s to the 1990s.

- In 1963, only 1.5% of couples had divorced before their fifth anniversary, 7.8% had divorced before their tenth, and 19% before their twentieth anniversary. By the mid-1990s this had increased to 11%, 25% and 38%, respectively.

- Since then, divorces have been on the decline. The percentage of couples divorcing in the first five years has halved since its 1990s peak. And the percentage who got divorced within the first 10 years of their marriage has also fallen significantly.

Divorces by age and cohort

What might explain the recent reduction in overall divorce rates in some countries?

The overall trend can be broken down into two key drivers: a reduction in the likelihood of divorce for younger cohorts; and a lengthening of marriage before divorce for those that do separate.

We see both of these factors in the analysis of divorce rates in the US from Stevenson and Wolfers.13 This chart maps out the percentage of marriages ending in divorce: each line represents the decade they got married (those married in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, 80s, and 1990s) and the x-axis represents the years since the wedding.

We see that the share of marriages ending in divorce increased significantly for couples married in the 1960s or 70s compared to those who got married in the 1950s. The probability of divorce within 10 years was twice as high for couples married in the 1960s versus those who got married in the 1950s. For those married in the 1970s, it was more than three times as likely.

You might have heard the popularised claim that "half of all marriages end in divorce". We can see here where that claim might come from - it was once true: 48% of American couples that married in the 1970s were divorced within 25 years.

But since then the likelihood of divorce has fallen. It fell for couples married in the 1980s, and again for those in the 1990s. Both the likelihood of divorce has been falling, and the length of marriage has been increasing.

This is also true for marriages in the UK. This chart shows the cumulative share of marriages that ended in divorce: each line represents the year in which couples were married. A useful way to compare different age cohorts is by the steepness of the line: steeper lines indicate a faster accumulation of divorces year-on-year, particularly in the earlier stages of marriages.

You might notice that the divorce curves for couples in the 1960s are shallower and tend to level out in the range of 20% to 30%. Divorce rates then became increasingly steep throughout the 1970s; 80s and 90s, and eventually surpassed cumulative rates from the 1960s. But, since the 1990s, these curves appear to be falling once again, mirroring the findings from the US.

We don't know yet how long the marriages of younger couples today will last. It will take several decades before we have the full picture on more recent marriages and their eventual outcomes.

As we saw from data on divorce rates, in some countries - particularly richer countries such as the UK, US and Germany - divorce rates have been falling since the 1990s. This can be partially explained by a reduction in the share of marriages ending in divorce, but also by the length of marriages before their dissolution.

How has the length of marriages changed over time?

In the chart here we see the duration of marriages before divorce across a number of countries where this data is available. An important point to note here is that the definitions are not consistent across countries: some countries report the median length of marriage; others the mean. Since the distribution of marriage lengths is often skewed, the median and mean values can be quite different.14

So, we have to keep this in mind and be careful if we make cross-country comparisons. On the chart shown we note for each country whether the marriage duration is given as the median or mean value.

But we can gain insights from single countries over time. What we see for a number of countries is that the average duration of marriage before divorce has been increasing since the 1990s or early 2000s. If we take the UK as an example: marriages got notably shorter between the 1970s to the later 1980s, falling from around 12 to 9 years. But, marriages have once again increased in length, rising back to over 12 years.

This mirrors what we saw in data on the share of marriages ending in divorce: divorce rates increased significantly between the 1960s/70s through the 1990s, but have seen a fall since then.

We see a similar pattern in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and Singapore. However, there is still a significant amount of heterogeneity between countries.